Story no. 1

Pike Place Market

Pike Place Market opened on August 17, 1907. As many as 70 wagons quickly began gathering daily on Pike Place, a wooden roadway connecting First Street and Western Avenue. By the 1920s, the market bustled with activity, including many Japanese and Italian-American farmers. In 1971, a “Save the Market” campaign resulted in voter approval of a historic market district.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.10020

Story No.2

Victor Steinbrueck Park

Victor Steinbrueck was a Seattle architect known for his efforts to preserve Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market. This park in his name, located down the street, began as the Washington State National Guard Armory built about 1909. The Seattle Parks Department took ownership after a fire damaged the Armory. Market Park was re-developed and renamed in 1985 to honor Steinbrueck’s contributions to the city.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.8230

Story No.3

Home for Mariners

The Seamen’s Institute opened in 1904 as a home for sailors and mariners. This photo, taken on a rainy day around 1906, shows the outside of the Seamen’s Institute on Western Avenue. Residents would have had a good view of the bay and waterfront from porches at the rear of the building. Their home was located right behind Pike Place Market.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.7694

STORY NO. 4

Laundry Service

In the early 1900s, laundry service was delivered with horse-drawn wagons. This driver and his horse worked for Queen City Laundry, located at First and Bell Streets. Behind the wagon, you can see a large building with the sign The Brenner at 2031 First Avenue.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Early Seattle Photograph Collection, 2014.59.87

STORY NO. 5

Union Stables

Built in 1910, Union Stables, located down the street, was once the home of 300 working horses. Today, it’s a unique office and retail site. The original carriage door entries at the center of the main façade have been preserved, along with the heavy timber and masonry construction. Union Stables is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.8730.2

STORY NO. 6

Native Gathering

A historic Duwamish community once flourished along the Elliott Bay waterfront. But shortly after Seattle became a city in the 1860s, Native people were banned from living near the center of town. As pictured in the 1880s, the foot of Bell Street became a gathering place for Native workers and traders on the outskirts of the city.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Lantern Slide Collection, 2002.3.71

STORY NO. 7

Belltown Cottages

Early Belltown was industrial, with canneries, mills and other waterfront businesses. In 1916, worker housing included small cottages with indoor plumbing and electricity. Three of the original six 20 x 24-foot cottages, now designated Seattle Landmarks, remain on Elliott Avenue between Wall and Vine Streets.

Photo credit: Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, 150046

STORY NO. 8

Building the Belltown Look

In the late 1800s, the construction of three brick buildings on First Avenue from Wall to Bell set the stage for the Belltown look: the Austin Bell (middle of the three tall buildings pictured above), the Barnes, and the Hull. These buildings, all on the National Register of Historic Places, still provide a powerful influence on Belltown’s architectural identity.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.10038

STORY NO. 9

Belltown Records

Capitol Records, the first West Coast-based record label of note, had a distribution center at the southeast corner of First Avenue and Bell Street. This photo was taken in 1946. Belltown was also the location for the hand record-pressing plant Morrison Records in the 1950s.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.16192.3

STORY NO. 10

Film Row

Belltown was once a long-time hub of film exchanges—miniature theaters used by motion picture studios to show the latest films to theater representatives. As many as 19 film exchanges and motion picture distributors existed in Belltown from the 1910s to 1980s.

Photo credit: Washington State Archives

STORY NO. 11

Belltown Unions

Beginning in the 1950s, Belltown was a regional hub of labor unions, especially those associated with maritime industries. At least eight unions called Belltown home. The Labor Temple (originally Sixth and University, shown here, now First and Clay), and Sailor’s Union of the Pacific (First and Wall) were two of the largest union halls.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.7913

STORY NO. 12

Belltown Street Names

William Nathaniel Bell (1817–1887) was an Illinois farmer who came west to claim 320 acres of Seattle land in 1852. His land claim later became the neighborhood of Belltown. William named Bell Street after his family. He also named Olive Street, Olive Way, and Virginia Street after his two daughters. Stewart Street was named for Olive’s husband, Joseph H. Stewart.

Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, POR1346

Viaduct and Battery Street Tunnel

STORY NO. 13

Viaduct and Battery Street Tunnel

The monumental Highway 99 Viaduct once defined Seattle’s waterfront. Until its closing in 2019, more than 90 thousand vehicles traveled daily through the 3,140-foot Battery Street Tunnel. Today, vehicles travel deep beneath Belltown in a two-mile replacement tunnel that daylights near the north portal of the old Battery Street Tunnel.

Photo credit: Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, 44458

STORY NO. 14

Seattle Swing

During the 1930s and ’40s, the Trianon Ballroom was the place for swing. Big bands and artists such as Duke Ellington, Guy Lombardo, Quincy Jones, and Ray Charles all performed at 2505 Third Avenue. A silver clamshell hood sheltered the bandstand, and tropical scenes decorated the walls. More than 5,000 dancers enjoyed the largest ballroom in the Northwest and its springy maple floor.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Al Smith Collection, 2014.49.002-029-0118

STORY NO. 15

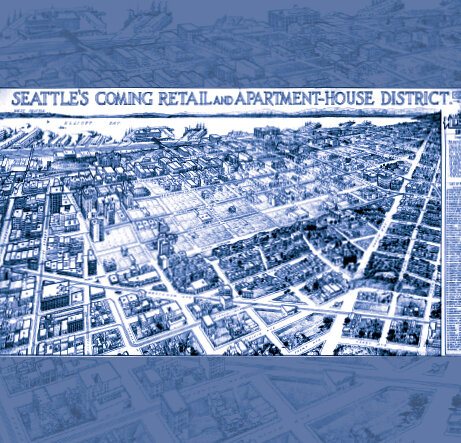

Belltown Growth

Belltown has grown in spurts since its founding in the late 1800s. In the 1920s it was regraded and promoted as a retail district. Recent growth includes office development in the 1970s and ’80s and residential apartments in the 1990s. The tech boom beginning in the early 2000s added another chapter with many newer residential towers.

Photo credit: Dudley Stuart

STORY NO. 16

Belltown Fire

On June 10, 1910, only 21 years after the Great Seattle Fire, a blaze consumed the waterfront side of Belltown. The fire began about 10:30 p.m. when the spark of a passing locomotive ignited materials at Galbraith, Bacon & Co. The fire burned a warehouse and stable before spreading north and east for 13 square blocks. Rain and quieting winds helped control the blaze.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.8649.1

STORY NO. 17

Modernizing Fire Stations

In 1921, Seattle built several new firehouses when the Fire Department switched from horse-drawn fire equipment to motorized trucks. Fire Station No. 2, at Fourth Avenue and Battery Street, was one of these modernized stations.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.2210

STORY NO. 18

Belltown Sound

Belltown has been home to Seattle’s music scene since the 1920s, when several ballrooms became popular venues for jazz, swing, and big band. Belltown is the original home of Sub Pop Records, renowned in the recording industry. World-famous names recorded here include R.E.M., Soundgarden, Nirvana, Heart, and Pearl Jam, pictured above in 1991.

Photo credit: © Lance Mercer

STORY NO. 19

First Women’s Housing of Seattle

The Franklin Apartments, built at Fourth and Bell Streets in 1918, was one of the first places in Seattle to offer housing for single women. Before then, it was considered improper for women to live alone. Social norms changed with the city’s growing demand for workers, including women living on their own.

Photo credit: Friends of Historic Belltown

STORY NO. 20

The Monorail

Built for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, the Monorail is a now a historic landmark. Its bold concrete platforms and elevated tracks create a striking physical presence as well as a distinct boundary between Belltown proper and the Denny Triangle neighborhood.

Photo credit: MOHAI, 1994.40.1

STORY NO. 21

The Regrade

Belltown was built next to Denny Hill and confined to a narrow shelf of land between the shoreline and slopes. But the City of Seattle decided to take down the hill in one of the largest earthworks ever accomplished. Completed in five projects over 33 years, the regrade literally paved the way for Belltown’s expansion to the east.

Photo credit: Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archive, 3637

STORY NO. 22

Sacred Heart Church Convent

Sacred Heart Church, established in 1889, was Seattle’s second Catholic church. In 1899, the building was completely destroyed by a fire, most likely due to arson. A reconstructed Sacred Heart was dedicated in 1900 in the same location, but in 1929, the building became a victim of the Denny Regrade project. The bell tower of the Denny School is visible on the right side of this photograph.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.3565.1

STORY NO. 23

Bob Murray’s Dog House

The Dog House was a popular Seattle hangout from the 1930s until it closed in 1994. Located at the corner of Seventh and Bell Streets, the venue was open 24 hours a day and offered nonstop music, food, and beverages. The establishment was run by Bob Murray and Laurie Gulbransen, whose motto was “All roads lead to the Dog House.”

Photo credit: MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.11356

STORY NO. 24

A Local Vibe

Belltown has a rich history of supporting businesses catering to locals, including taverns and bars. This local vibe remains a key component of Belltown life. In the early years, local laborers including loggers, fishermen, sailors and longshoremen frequented Belltown bars. Beginning in the 1970s, patrons shifted to local artists, musicians, and service industry workers. Over time and neighborhood changes, Belltown has always been a place to gather.

Photo credit: Friends of Historic Belltown

STORY NO. 25

Downtown Service

For most of the 20th century, Belltown was a service district to downtown Seattle. It provided light industry, printing, auto garages, and laundries for a thriving downtown, as well as workforce housing. This photo depicts a gas station attendant near the pumps at the Gilbert Station, located near Eighth and Stewart Streets.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 1986.5.11753

STORY NO. 26

Presidential Visit to Seattle

On July 27, 1923, President Warren G. Harding visited Seattle on a 40-day tour of the Western U.S. As it turned out, Harding’s speeches during his six-hour Seattle stay were not only the last of the trip, but of his life. The 29th President died of a heart attack only a few days after leaving the city.

Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, CUR1419

STORY NO. 27

Westlake Automobiles

As the automobile industry boomed, the Westlake area became Seattle’s car dealership center. By 1939, some 40 automobile-related businesses could be found on the 12-block stretch of Westlake near South Lake Union. This photo, taken around 1949, shows a Chevy parked outside Westlake Chevrolet on Westlake Avenue near Lenora Street.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.16931

STORY NO. 28

Seattle’s Oldest Park

Denny Park, located across the street, is Seattle’s oldest park, originally created as a cemetery. In 1884, the graves were moved and the park was landscaped to hold planting beds, swings and playing fields. During the final phase of the Denny Regrade, the park was lowered by about 60 feet.

Photo credit: Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, 28967

STORY NO. 29

Reverse the Regrade

Architect Jerry Garcia’s 2006 proposal, titled “Make Believe,” would have rebuilt the earthen Denny Hill using leftovers from a waterfront tunnel. His vision was a large, open lawn and paths, a natural amphitheater, and a pavilion with a permanent exhibit on Denny Regrade history. However, Garcia decided not to campaign for this, and the idea did not move forward.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Lantern Slide Collection, 2002.3.443

STORY NO. 30

Biotech

South Lake Union has attracted biotech companies since the 1970s. At first, companies were drawn to the area’s inexpensive land. The Hutch, Seattle BioMed, PATH (located up the street), Institute for Systems Biology, and The Allen Institute for Brain Science are among those who’ve been or remain in the area. This 1991 photo shows Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center under construction.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, 2000.107.175.09.01

STORY NO. 31

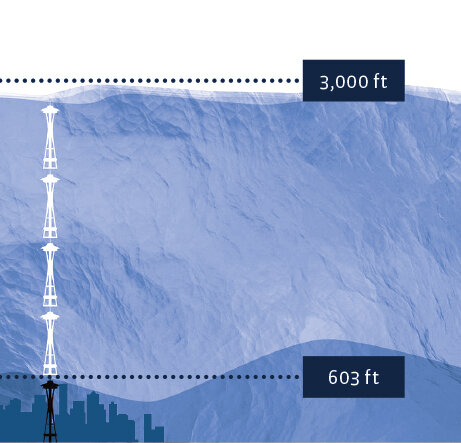

Ice Age

A mere 17,000 years ago, the Cordilleran Ice Sheet covered what’s now Seattle and a large part of Western Washington. The glacier towered 3,000 feet high, about the height of five Space Needles. The Seattle area was an estimated 275 feet lower during the glacier’s last advance.

Photo credit: Courtesy Burke Museum

STORY NO. 32

Takamori Sculpture

You’re standing near Akio Takamori’s cast aluminum sculptures, “Young Woman, Girl and Mother and Child.” Takamori (1950–2017) was born in Nobeoka, Japan and moved to the United States in 1974. For 21 years, he taught ceramics at the University of Washington. His work has been displayed around the world.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the artist

STORY NO. 33

On Native Land

You are standing on occupied land of the Duwamish, Suquamish, and Coast Salish people. It is our collective responsibility to recognize that this land is the traditional territory of Indigenous peoples and pay respect.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Seattle Historical Society Collection, SHS2174

STORY NO. 34

Bogue Plan

In 1911, engineer Virgil G. Bogue created an elaborate plan for Seattle’s expansion after the completion of the Denny Regrade. His vision included new arterial streets, highway tunnels, raised railways, waterfront designs, housing sites, and a civic center. The plan would have cost tens of millions of dollars, and Seattle voters failed to approve it by a two-to-one margin.

Photo credit: Seattle Municipal Archives, 54

STORY NO. 35

Immanuel Lutheran Church

Looking east, you can see the spire of historic Immanuel Lutheran Church at 1215 Thomas Street. This church was built in 1907 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. An original 12-foot rose window graces its sanctuary space, with colored glass added on the centennial anniversary. Immanuel Lutheran has been active in the community since its founding.

Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, SEA1691

STORY NO. 36

Seattle Commons

In 1991, the Seattle Commons was proposed to your west as a 61-acre park running from Westlake Center to Lake Union. It was to be bordered by high-rise, high-tech development. The project got its start when Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen lent the Commons campaign $25 million to buy land. Allen’s loan would be forgiven if voters approved another $111 million, but the project was twice voted down.

Photo credit: Courtesy Seattle Municipal Archives, 338

STORY NO. 37

Seattle’s Streetcars

On the tracks across the street you will find the South Lake Union Streetcar, which initiated the return of streetcars to city streets in 2007. This line runs between the Westin Hotel in downtown Seattle and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center by Lake Union. Seattle’s first electric streetcar service began in 1889 and quickly grew to many separate lines linking outlying neighborhoods to downtown Seattle.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Seattle Historical Society Collection, SHS7701

STORY NO. 38

Mammoth Tusk

The largest and most complete mammoth tusk ever found in Seattle was unearthed at the bottom of a South Lake Union construction site in February 2014. The 8.5-foot-long fossil is believed to be a Columbian mammoth tusk estimated at 20,000 years old. It was donated to the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington.

Photo credit: Courtesy Burke Museum

STORY NO. 39

Transporting Coal

Seattle opened its first rail line in 1872. The Seattle Coal and Transport Company used the line to carry coal from a dock on the south end of Lake Union to coal bunkers on Elliott Bay, roughly along the route of Westlake Avenue North. A series of tugboats and barges brought the coal to Lake Union from Newcastle mines.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Lantern Slide Collection, 2002.3.437

STORY NO. 40

Lake Union Shoreline

An original settlement for the Duwamish people, South Lake Union is one of the oldest locations of human development in the region. The shoreline has changed significantly over time. After European-American settlement, Denny’s Mill modified the shoreline with sawdust. In the mid-1900s, the land was filled in further for a Naval Reserve complex.

Photo credit: MOHAI, John Vallentyne Photographs, 2009.23.57

STORY NO. 41

An Ancient Trail

For centuries, Native people traveled a trail between what’s now called Lake Union and Elliott Bay. In 1879, the trail was converted to a boardwalk to access Denny’s Mill on Lake Union. This 1884 map shows Elliott Bay in the foreground and Lake Union to the left. Today, the Market to MOHAI trail maintains a pedestrian connection between the waterfront and Lake Union.

Photo credit: MOHAI, Henry Wellge, 1947.83.1

STORY NO. 42

Cheshiahud

In the days before roads, Cheshiahud was a renowned Duwamish chief and travel guide to Lake Union, Lake Washington, and Lake Sammamish. He had a cabin and a potato patch near the foot of what is now Shelby Street by the Montlake Bridge. The paved loop around Lake Union is named in his honor. This image shows Cheshiahud with his wife Tleboletsa.

Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, NA591

STORY NO. 43

From Automobiles to Research

William O. McKay established his Ford and Lincoln dealership at 609 Westlake Avenue North on the west side of the street in 1923. The building was a premier example of Art Deco in Seattle. It existed as a luxury car dealership until 2015, when the Allen Institute for Brain Science opened in its place. The new structure features a section of the original terra cotta façade.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.13401.1

STORY NO. 44

Wilson’s Wood Row

When the United States entered World War I, Seattle’s shipyards boomed building wooden transport ships. Post-war, many of the Navy’s surplus ships were stored in Lake Union. The “mothballed” fleet was nicknamed Wilson’s Wood Row after wartime president Woodrow Wilson. This image shows surplus boats in Lake Union as seen from Capitol Hill.

Photo credit: MOHAI, PEMCO Webster & Stevens Collection, 1983.10.2261.1

STORY NO. 45

Western Lumber Mill

One of Seattle’s first European-American settlers, David Denny, purchased land south of Lake Union. In 1882, he opened the Western Mill on the lake’s southern shore and a small community soon grew up around the lumber yard. By the end of the 1880s, streetcars and roads had been built, and the area lost its rural look.

Photo credit: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, LAR303

STORY NO. 46

Naval Reserve Armory

The Naval Reserve Armory was completed in 1942 using federal funding. This massive concrete building designed by William R. Grant and Marcus Priteca features Art Deco and Moderne features partially held up by wood pilings. In 1998, a disestablishment ceremony of the Naval Reserve Armory took place and the building is now home to the Museum of History & Industry.